Games referenced in paper below:

Natalie Bookchin,

Intruder

(http://www.calarts.edu/~bookchin/intruder)

Metapet

(http://metapet.net/)

Esc to begin,

Font Asteroids

(http://www1.zkm.de/~bernd/etb-os/net-condition/projekte.html)

Mouchette, Lullaby for a Dead Fly

(http://www.mouchette.org/fly/)

Sissyfight

(http://www.sissyfight.com/)

John Klima, Go Fish

(http://www.cityarts.com/lmno/postmasters.html)

Art games and Breakout: New media

meets the American arcade

Tiffany Holmes

tholme@artic.edu

Summary

This paper explores how the interactive paradigms and

interface designs of arcade classics like Breakout and Pong have been incorporated

into contemporary art games and offer new possibilities for political and cultural

critique.

Introduction

Breakout, the first mass marketable video game, was a

defining game experience for many in the 1970s.It positioned Atari at the forefront

of the game industry under the business union of Apple Computer’s founders, Steve

Jobs and Steve Wozniak.The long-term potency of game culture has since been firmly

established.In 2001, twenty-five years after the original version was released,

MacSoft released a new Breakout that incorporated kidnapping narratives, paddle

angling, and power-ups into the classic game.Also last year, the release of two

powerful new consoles, Microsoft’s XBox and Nintendo’s Game Cube, redoubled the

hype surrounding the obsession with gaming.In 2000 the video gaming industry surpassed

Hollywood in gross annual revenues to become the second largest entertainment

industry after music in the United States.[1]

Retro-styled Art Games

The immense success of the gaming industry, now global,

has inspired droves of artists to create new works that pay homage to arcade classics

of the 1970s and 1980s. For example, Natalie Bookchin incorporates interactive

tropes from Pong and Space Invaders into work that demands both manual dexterity

and theoretical reading. Bookchin’s game, The Intruder, adapts a short

story by Jorges Luis Borges about the life of two brothers who fight for the mysterious

woman both desire. Another art game project, Font Asteroids, allows users

to select information itself as the enemy.The German collaborative, Esc to begin,

designed the game to look much like the arcade classic. After selecting a target

URL, the text from that web site becomes the interplanetary debris that you must

shoot away. Like the original Asteroids, the words in Font Asteroids

break apart into smaller and smaller fragments—in this case, prefixes, suffixes,

and roots.

The exciting works of these game-influenced artists have begun

to make their way into elite museums. Several exhibitions showcasing art games were

organized in the last three years alone: Mass MOCA’s “Game Show”, the San Francisco

MOMA’s “010101: Art in Technological Times,” the Walker Art Center’s “Beyond

Interface,” and the Whitney Museum’s “Bitstreams.” Overall, the proliferation

of works by artist gamers in conjunction with the sweeping accomplishments of

the gaming industry has had a reverberating impact on a variety of cultural

institutions: art museums, grant organizations, and of course, art schools

Fanatical gamers and art schools

The tremendous success of the commercial gaming industry

has helped to shape curriculum at universities and art schools around the world.

Espen Aarseth, editor of the journal Game Studies, contends that computer

games, as a cultural field, will carve out new territory for graduate programs.[2]

However, many art students seek only the computer and technical skills that will

enable them to secure design and programming jobs at game development companies.

These students often sacrifice valuable classes in political theory, women’s studies,

and economics among others to obtain a solid grounding in software manipulation

and code writing. Educators thus face a tremendous challenge in striking the proper

balance between technique, craft, and theoretical knowledge in game-related media

arts courses at both introductory and advanced levels. The largest challenge remains

satisfying student-driven demands for technical skill while maintaining the intellectual

and artistic integrity of art education.

Objectives of paper

My own intervention in the historical context elaborated

above involves a critical reading of the current surge in game-inspired interactive

art works. I began to investigate this new genre while developing a course curriculum

at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In “Interactive Multimedia: Breaking

out of the Arcade,” intermediate-level students explore the history of art games,

beginning with the Surrealists and Duchamp and progressing through the recent

online experiments released by jodi.org. The principal assignment asks each student

to invent a unique version of Breakout that showcases their ability to incorporate

an individual narrative and concept within an arcade-style form.

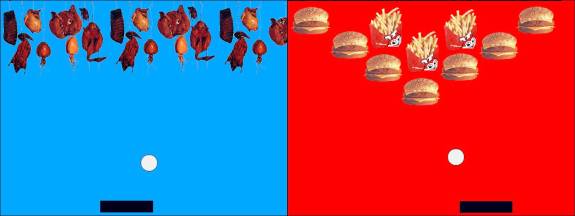

Figure 1: Breakout animation still, Lidia Wachowska, 2002.

The course inspired a series of discoveries that enriched

both my teaching and my own studio practice.First, appropriating the game form

for art making allowed students to explore different models of space. Cultural

theorists like Michel Foucault—whose Panopticon makes for a striking comparison—and

Lev Manovich, among others, provided students with theoretical readings of power,

space, and storytelling. “Narrative and time itself are equated with movement

through 3-D space,” Manovich writes, “progression through rooms, levels, or worlds.”[3]Second,

in the art-making part of the course, students produced surprising variations,

both serious and humorous, on the familiar Breakout theme.In one game, the bricks

became government currencies.In another, the blocks took on human qualities, enacting

behaviors labeled “mother,” “magician,” and “bouncer.” One ambitious student,

interested in the idea of game play rooted in the act of consumption—as evidenced

in arcade classics like PacMan and Burgertime—chose to make her game begin with

a survey that documented participants’ food preferences (Figure 1). At the conclusion

of the survey, the player is presented with an array of distasteful food from

which they must escape. Here food becomes a medium that imprisons. In advising

these student projects, I realized that the art game genre provides a new vehicle

for artists to articulate political and cultural commentary. Third, and finally,

I incorporated the Breakout trope into my own work, an installation called <a_maze@getty.edu>

for a special exhibition of optical toys at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los

Angeles.

The remainder of this paper will explore each ofthese subjects in turn: video gaming and models of space, art games as

spaces for cultural critique.

SpaceWar: Gun Play on the Cartesian Grid

The defining element of both mainstream video games and

game-inspired art is the organization of play through and across space. The spatial

aesthetic and spatial language of both shape the meaning of experience. While

there are many different types of video games, the great majority are first person

shooter epics with plots based on militaristic combat. SpaceWar, Tank, and Space

Invaders are early examples of shoot ‘em-up contests in which, as the Beatles

said, “happiness is a warm gun.” Breakout is one version of the shooter epic,

located within a prison complex. As illustrated in the arcade marquee from 1976,

the player assumes the role of a convict attempting to escape by smashing through

a brick wall with a mallet. In the video game, this narrative was formally simplified

as a small rectangular paddle that the user guided to hit a ball that chipped

away at a grid of jewel-toned bricks. Despite the imaginative narrative context,

the game was essentially a flat, non-dynamic grid.

In striking contrast to the two-dimensional simplicity of Breakout, the most recent

generation of video games offers a version of hyper-reality in which story and

space are three-dimensional, dynamic, and experientially real. On March

10, wedding bells rang online for Mr. Dong-jun Choi and Ms. Yousun Jang. The couple

made their vows of commitment in the context of the multiplayer game environment

that both fondly remember as their courting ground. The two lovers met online

competing in Blizzard Entertainment’s Diablo II, a role-playing adventure game

in which participants choose characters and battle the forces of evil from their

comfortable living rooms. The experience of Mr. Choi and Ms. Jang is part of an

emerging dynamic familiar in the web-based video gaming subculture. More and more

couples are meeting virtually in their game communities and celebrating their

romantic successes with faraway friends and fellow competitors. The game world

has evolved from the geometric abstractions of Breakout to extensions of an individual’s

daily pathways and travels through space, an extension of real life. Virtual

spaces provide portals for exploration and discovery as well as a sense of amazement.

Steven Poole, author of Trigger Happy, contends that the “aesthetic emotion

of wonder” is the “jewel” of the game-playing experience.[4] Certainly the sheer plasticity of

the spatial environment is a primary lure for the designers of the games as well

as those actively playing. The newest games feature sprawling swaths of territory

on which to battle. The frontier of the game world is limitless, contingent only

on the speed and memory of the gamer’s computer or console. On the Internet, Diablo

II boasts “four different, fully populated towns complete with wilderness areas

as well as multiple dungeons, caverns, and crypts in every town for players to

explore.”[5] Ultra-realistic

battles between the forces of good and the forces of evil take place in a sprawling

land empire. Games like Diablo II and Starcraft are especially popular in Japan

and Korea, where domestic space remains quite small and panoramic mountain vistas

and babbling brooks are several hours away by rail.

Despite the extreme popularity of the newest cutting-edge graphics engines, game

environments suffer from two limitations that complicate their relationship to

contemporary new media-based art. First, they remain the same Cartesian enclaves

clogged with familiar structures: skyscrapers, towers, trees, boulders, dams,

and dungeons. The spatial aesthetics of video games have evolved from the abstract

beauty of bouncing squares to the realism of metal-sheathed guns, but they celebrate

rather than transcend the boundaries of Cartesian spatial logic. Second, and perhaps

more obviously, game culture remains wedded to a first-person narrative of violence

and point acquisition. The win/lose dichotomy and the shooter aesthetic and subjectivity

that dominate the industry offer an impoverished model of space, their “virtual”

experience notwithstanding.

The issue of who controls the spatial aesthetics of commercial video games is

complicated. The limiting factors associated with consumer economics, mathematical

models, and popular taste combine, resulting in the formation of surprisingly

similar structures for the putatively cutting-edge graphical worlds: futuristic

cities, Gothic churches, medieval castles. The Cartesian perspective is the most

straightforward to generate mathematically, but the hardware industry also has

a vested interest in the popular penchant for ever-realer spaces. And PC manufacturers

and console developers rely on the game software’s demand for speed to spur sales.

Joystick Nation author JC Herz describes the parasitic relationship that

develops between the computer hardware and the game development industry: “The

only thing that will push a computer to its limits is a game. No one admits it

but no one needs a new computer to do a spreadsheet programme or Word document.”[6]

She asserts that games ultimately manipulate and rule the PC industry: “Unless

you are in a military installation, the most demanding application on any computer

will be a game.”

However produced, the video game industry’s reliance on Cartesian realism sits

in striking contrast to the contemporary art world. Over a century ago, painters

abandoned Cartesian space after mastering the process of manipulating pigments

to form a perceptively accurate space. Fine art collectors, including museums,

have for decades defined gallery-quality art in terms of “high brow” aesthetics

that honor the traditions of minimalism, conceptualism, and abstract expressionism.

Video games, in contrast, constitute a popular, “low brow” form of entertainment

that takes realism for granted. Yet as games reenter the immaculate spaces of

museums, they force a new dialogue about what constitutes an “art space” as opposed

to a purely “game space,” resurrecting long-standing debates about high and low

culture, high and low art.

Artists have taken notice of the proliferation of the commercial game medium and

are experimenting with not only the spatial aesthetic but also the mode of game

play. They are attempting to vary the characters and to introduce narratives with

game outcomes and objectives that resist the assumed spatial and narrative logic

of a traditional game. Feng Mengbo, for instance, began his work in the art games

arena by recasting the popular Nintendo character Mario as Mao Zedong. His first

piece, The Long March Goes On, locates the game objectives of the Mario

Brothers classic within the contentious relations between his homeland, China,

and the West. Throughout his life—as a child of the Cultural Revolution and a

young adult during the events at Tianamen Square—Mengbo witnessed oscillating

degrees of openness between China and the West. The artist chose to make work

about the opposing ideologies shaping Chinese society: revolution and modernization.

In selecting the highly structured and delimited game format for this politically-charged

subject matter, the artist grounds his cultural critique in a pop medium that

is itself an emblem of western consumerism and modernization. In his most recent

work, Q4U, Mengbo writes a patch for the Quake game that features the artist wielding

a camera in one hand, a rifle in the other. The frag-or-be-fragged excitement

so dominates game play that one ignores the specific identity of the enemy, the

artist himself. Perhaps the instantaneous forgetting is the slippage that is the

resonant point.

Space Invaders: Cyberfeminism and Artistic Practice

In the late 1990’s, women publicly laid claim to the crowded

territory of the male-dominated gaming world.As online games became increasingly

accessible, more women tried their hands at fragging, dueling, and role-playing.A

host of new organizations sprang up to create a safe and stimulating place for

women to experiment in trigger-happy cyberspace: Womengamers.com, Joystickenvy.com,

GameGal.com, Gurlgamer, GameGirlz, Grrl Gamer, and many, many more. Why this sudden

landslide of femme-only gaming communities? Single-mom "Aurora" Beal

confesses her motivation: “When I started the GameGirlz site…my only goal was

to create a website where girls who were into games didn't have to wade through

the semi-nude pictures and scroll through the jokes only a guy could appreciate.”[7]Like

the quilting circles of yesteryear, women have created their own spaces of retreat

to share conversation that spans a variety of topics beyond game reviews and strategy.

Unfortunately, as theorists like Faith Wilding have pointed out, this phenomenon

of “cybergrrl-ism” is afflicted with a blinding net utopianism. Wired women participate

in an ambiguous feminist politics by adopting the “if you can’t beat ‘em join

‘em” attitude with regard to online gaming. However, in the real world, women

are not in visible positions of leadership in the critical venues of research

and development in new technologies—neither in business and industry nor in the

university settings of science laboratories and art schools. Trigger-happy girl

gamers might believe that Quake game patches written to produce custom female

tattooed skins inject a certain feminist presence into cyberspace.

More and more female bodies are invading the spaces of popular entertainment,

yet they share the same buff bodies and aggressive personalities. The online explosion

of the riotous cyberpunk culture in the mid to late nineties was followed by a

resurgence of a fighter chick character in both television and Hollywood productions.

The entertainment industry labored to establish women as players in a larger culture

of sanctioned violence. Buffy, Zeena, the Matrix’s Trinity, and Charlie’s

Angels are but a few examples of the new warrior heroine. Women who do not play

games can thus passively endorse the commodification of violent gesture as a symbol

of girl power. Yet for the most part, both women who “game” and women who watch

participate in a larger narrative of, at best, ambiguity, and, at worst, submission

that their overwhelming desire to beat the boys at their own game promotes.

Figure 2: The Intruder, animation still, Natalie

Bookchin, 1999.

To develop a feminist politics and activist trajectory

in cyberspace, girls need to develop their own games. While this remains a marginalized

project in the game industry, artists have pursued it with vigor. The emerging

art game genre provides artists with a new structure to hack masculinist institutions

and power hierarchies. Perhaps the best current working example of the “low art”

form being elevated to “high art” is Natalie Bookchin’s aforementioned The

Intruder, an experimental adaptation of a short story by Jorge Luis Borges.

The game changes readers into players who move through the linear narrative by

shooting, fighting, ramming, and dodging objects. Bookchin mines the arcade classics

to tell the story of two brothers who fall in love with the same woman. One of

the most interesting moments in the game happens in the Pong screen, in which

the viewer and the computer compete for points by batting a female icon back and

forth. The war takes place atop a field of flesh—photographs of a nude female

body appear each time one of the players temporarily takes possession of the woman.

The “field” metamorphoses from skin into turf—the body becomes territory to possess

in a game of football. The story advances when one man tackles the other. Here,

the narrator comments: “They preferred taking their feelings out on others.”[8]

Computer games have traditionally provided a culturally sanctioned outlet for

male killing and sexual fantasies. Gamers can only advance in The Intruder

by perpetrating violent gestures. This novel, first person shooter structure invites

gamers to see how popular computer games perpetuate masculine ideologies of spatial

conquest, combat fantasies and sexual domination.

New spatial paradigms and modalities of play in the art game genre raise additional

questions about the permissibility of violent conduct by introducing new forums

for injustice into the online world. For example, in Lullaby for a Dead Fly,

the artist Mouchette invites the gamer to kill a fly with a click of the mouse.

In this simple interaction, the fly reminds us that a click represents a choice,

an assertion of power in her own elegiac song: “You clicked on me, you killed

me.” Likewise, Eric Zimmerman’s Sissyfight, an immensely successful project

produced by the online magazine Word.com, asks participants to consider

the violence of words in a multiplayer online game set in the context of a simple

two-dimensional playground. Players participate in a wickedly humorous catfight

with other girls, using teases and tattles to break down the self-esteem of other

players and drive them away. Perhaps to its detriment, the game allows players

to scratch and grab in their quest for points. The all-girl characters and witty

repartee, not the violent combat, make the game novel.

As artists continue to work collectively to recontextualize and reinvent female

characters, so too must industry and gamers re-imagine the diverse cultural possibilities

of game space. The popular excitement around the culture of cybergrrlism reveals

a positive new interest in carving out an active space for women to communicate,

congregate, and play online. Yet in the absence of roles for women in cyberspace

different from those assigned to or by men, there remains a profound ambiguity.

As history shows us, today’s internet originated as a system to serve war technologies.

War games are but a fantastic extension of militaristic laboratories. In the future,

women must claim their territorial rights not only as players of games but as

producers, designers, and developers of technologically mediated experiences like

games—games that are not war games, games that steer us toward a more engaged

relationship with complex female characters that refine today’s definitions of

cyberfeminism. Today’s art games and multimedia projects are opening the door

to a more nuanced description of virtual spaces that embrace a diverse array of

characters and modalities of play.

Conclusion

Game-inspired art works represent a vitally important

emerging form that explores new modes of visualizing space and time, and from

these investigations emerge new narrative models for interaction, new formats

for cultural and political critique, and alternative interfaces for game play.

John Klima’s multimedia installation, Go Fish, is a novel first-person

shooter game with real-time consequences —the death of a goldfish.[9]

Housed in a retro-styled arcade cabinet, the game asks participants take moral

responsibility for their trigger-happy behaviors. Arcangel Constantini’s new game,

Atari Noise, features a hacked Atari 2600 that functions as an audiovisual

noise pattern generator—a very abstract look at the spatial possibilities inherent

in the art game genre.

From the straightforward Breakout sequence to the complex 3-D landscapes of games

like Quake, video games have collided with the world of art to forge a new genre

of art games. As artists, we have much more to explore in the game format in terms

of both spatial innovations and also game play. It is our responsibility as artists

to “break out” our software design abilities to continue to refine, via formal

structure and cultural commentary, the realm of game architecture to create new

interactive structures for expression.

[1] Mark

Tribe and Alex Galloway, “Net Games Now,” Rhizome, April 29, 2001, http://rhizome.org/print.rhiz?2632.

[2] http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/editorial.html.

[3] Lev Manovich, The Language

of New Media, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), p.245.

[4] Steven Poole, Trigger Happy:

Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution, (New York: Arcade Publishing,

2000), p.226.

[5] Advertisement for Diablo II:

http://www.blizzard.com/diablo2/.

[6] JC Herz, Go Digital,

BBC news interview, August 4, 2001, http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/sci/tech/newsid_1504000/1504718.stm.

[7] Interview by Geri Wittig and

Max Hardcore, http://switch.sjsu.edu/web/v5n2/interview.html.

[8] http://www.calarts.edu/~bookchin/intruder.

[9] Klimas’s Go Fish was

exhibited at Postmasters Gallery, NYC, 2001: http://www.cityarts.com/lmno/postmasters.html.